A nuclear future means clean, reliable and economic electricity; yet fossil fuels reign supreme

This past month, following the fourth anniversary of the Fukushima accident, it is good to see there is less emphasis on the nuclear accident and more discussion of the significant natural disaster – the tsunami and earthquake that killed some 20,000 and destroyed so much, leaving 300,000 homeless. It is now clear that the nuclear accident will not be a cause for radiation-induced cancer, food is not contaminated, and most people can return to their homes should they so desire. While there continues to be a big mess to clean up and many important lessons in managing nuclear accidents to learn, there is no disaster in terms of either immediate or long-term health impacts. Yet we still see news such as was reported this week- that Fukushima radiation has reached the west coast of Canada – one then has to read the report to find out it is so minute as to be a non-event.

So now 4 years on, if we look at China one could conclude the nuclear industry is booming. CGN reported 3 new units were connected to the grid in March, with 2 more expected to be connected within this year. Overall China now has 24 units in operation and another 25 under construction targeting 58 GW in service by 2020 and then accelerating from there to bringing as many as 10 units per year into service in the 2020s targeting about 130 GW by 2030. Two new reactors have just been approved in the first approvals for new units post Fukushima. In addition to this, China is now developing its Hualong One reactor for export as it strives to become a major player in the global nuclear market.

China Hongyanhe 3 completed

China’s commitment to nuclear power is strong and unwavering. An important reason for this rapid expansion is the need for clean air. Pollution in China is a real and everyday problem for its large population. The Chinese see nuclear power as path to ultimately reducing their need to burn coal and hence help the environment.

On the other hand, in Germany a decision to shut down some nuclear units in 2011 immediately following the Fukushima accident and to close the rest by 2022 has led to a large new build construction program of lignite-fired units to meet short term energy needs. With several under construction and some now in operation, coal is producing about half of Germany’s electricity. Keep in mind that these new plants will likely be in service until about 2050. This is while Germany supposedly is focusing its energy future on ensuring a cleaner environment using renewables. I would expect their goal would be easier to reach without a number of new coal-fired units going into operation to replace clean carbon free nuclear energy.

The lignite coal fired power plant Frimmersdorf

It is with these two extremes in mind that I noted when attending the Nuclear Power Asia conference in Kuala Lumpur this past January that while almost all South East Asian countries are planning to start nuclear power programs, they have had little success in getting them off the ground. Currently Vietnam is in the lead and countries such as Indonesia and Malaysia are continuing with their plans, but with little progress. For example, Indonesia has been talking about nuclear power for more than 30 years. With a need for 35 GW of new capacity in the next five years and an annual expected growth of 10 GW per year after 2022, it is easy to ask why a decision for new nuclear seems perpetually stalled while there has been no problem building new fossil plants.

While in Malaysia I couldn’t help but think – why is it so difficult to make a decision to invest in new nuclear plants, especially for first-time countries? Is it a fear of nuclear itself and the issues associated with public acceptance – or is it the commercial aspects whereby nuclear plants have relatively large capital expenditures up front raising financing and risk issues? Or, more likely, a combination of the two.

At the same time as decisions on new nuclear seem to be so difficult to take, literally hundreds of coal plants and thousands of gas fired plants are being built around the world. If the environment is actually important, why is it so easy to invest in fossil stations and so hard to invest in nuclear? One simple answer is the size of the global fossil industry. Countries like Indonesia and Malaysia have huge industries with fossil fuel development being an essential part of their economies. The public is comfortable with this industry and many either work in, or profit from the industry in some way. The same is even true in Germany, where coal and lignite mining is entrenched. While committed to reducing hard coal use over time, once again this is an important industry in the short term.

For a country looking at nuclear for the first time, like those in South East Asia, there has to be a strong base of support to get the industry off the ground. They need to be serious about their consideration of the nuclear option, not just dabbling with little real interest. While these countries have modest research and other programs, there is simply not enough going on nor a strong belief that there are no alternatives to garner the political support to move forward. Starting a nuclear program is a large undertaking and the fear of securing public support and concerns about safety and financial ability to support the program are paramount. This makes it difficult for decisions to be taken. A strong and committed view from within government is needed and this can only be achieved with a strong need for energy and an even stronger belief that the public is on side.

China has passed this milestone and now has a large and vibrant domestic industry. Government support is assured so long as the industry continues to thrive. To the Chinese, the issue is clear. Nuclear plants are economic and their environmental benefits are essential to helping solve their huge environmental issues. The Chinese have CONFIDENCE in their ability to deliver safe, economic and reliable nuclear power stations.

On the other hand, the Germans have decided their fear of nuclear is stronger and more urgent than their need to reduce their carbon emissions in the short term even though they had a large and strong domestic nuclear industry. In this case, Germany is an outlier and to this end they justify building new coal units even when their overriding goal is environmental improvement.

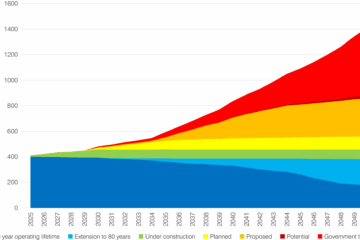

I am confident that nuclear plants will expand their already important role in the future electricity mix of the world and, as such, the industry needs to find new and innovative ways to make taking a nuclear decision easier. This includes ways to gain a higher level of public support, ensure that project risks are manageable and that costs can be kept under control. In some future posts, we will talk about some of these ideas and how we can unlock the global nuclear potential.

7 Comments

James Greenidge · April 12, 2015 at 9:19 pm

VERY good article. The Germans ought take a gander and read and see the contents! Also please probe on Greens trying to scare Africa from having nukes by razing wilderness and vistas for wind and solar farms! Keep up the good work!

James Greenidge

Queens NY

rod carrow · April 13, 2015 at 2:21 am

It has been surprising to see that Germany, with its impressive history of scientific and technological advances would embrace coal/lignite as an acceptable alternative to nuclear. I think it displays short term strategic thinking.

I expect that life cycle analysis of nuclear and coal technologies, involving factors such as occupational health and safety, air pollution and associated public health effects, global warming and other long term ecological effects such as ocean acidification would reveal that nuclear is clearly superior.

rennie caplan · April 13, 2015 at 10:37 am

i find that china is going strong with nuclear power

maybe one day germany will wake up

excellant article

Bill · April 13, 2015 at 7:11 pm

Wind and solar are proven to kill birds and bats, disturb wild animals and natural habitats, noise affecting nearby residents, visual impact of the development on the landscape.

On the other side, even taking in mind Chernobyl and Fukushima, even if compared to solar and wind, nuclear power has caused less fatalities, less lives lost, less environmental impact per unit of energy generated.

“In terms of lives lost per unit of energy generated, analysis has determined that nuclear power has caused less fatalities per unit of energy generated than the other major sources of energy generation.”

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nuclear_power

Greg Kaser · April 16, 2015 at 10:47 am

If you look at the list of countries with operating nuclear power plants on the World Nuclear Association website you will see that 10 countries have less than 3 reactors and 12 countries have 10 or more (and 8 are in between). We may think of them as divided between the technology testers and the committed (or in Germany’s case the no longer committed). Among the countries building nuclear reactors for the first time are several that may just be testing the technology. Among the 8 countries with fewer than 10 are 4 whose governments have already decided to phase out nuclear energy or appear to wish to do so (all of them in western Europe). My guess is that there are at least 24 committed countries with operating reactors and another 7 who seriously intend to construct plants in the future.

Milton, I think you are right when you emphasize government commitment. Some governments seem to have it and others not, and it may be more to do with confidence in the technology, as you say, than the economic factors (although these do, undoubtedly, play a part) .

Kinderhoff · April 16, 2015 at 3:53 pm

It would take the U.N. to declare an environmental emergency to preempt global warning in order for nuclear’s fortunes to change. Examine that route.

publius · April 24, 2015 at 1:53 pm

Speaking of Southeast Asia, what about the Philippine nuclear plant at Bataan?

There it sits, completed but never started up, a sort of Asian Zwentendorf. I have a strong mind to write to the Catholic Bishops’ Conference, confronting them on their opposition.

Comments are closed.