Let’s stop focusing on beliefs and really start communicating

How many discussions have you had today where either you or the other person thought carefully, and then said “here is what I believe….”? Believe is a strong word. It evokes personal values; and when something makes it to the level of a belief, it is often unshakeable.

There was a time when we didn’t talk like this. We gave our opinion, or our view on a topic. This was developed through learning, by listening to (hopefully) an expert or reading relevant information. An opinion meant this is what we think at the moment, and that should we learn more, we may change or evolve our position. Now our views on almost every topic need to be elevated to the level of “belief”. And as we know, we don’t change our beliefs easily.

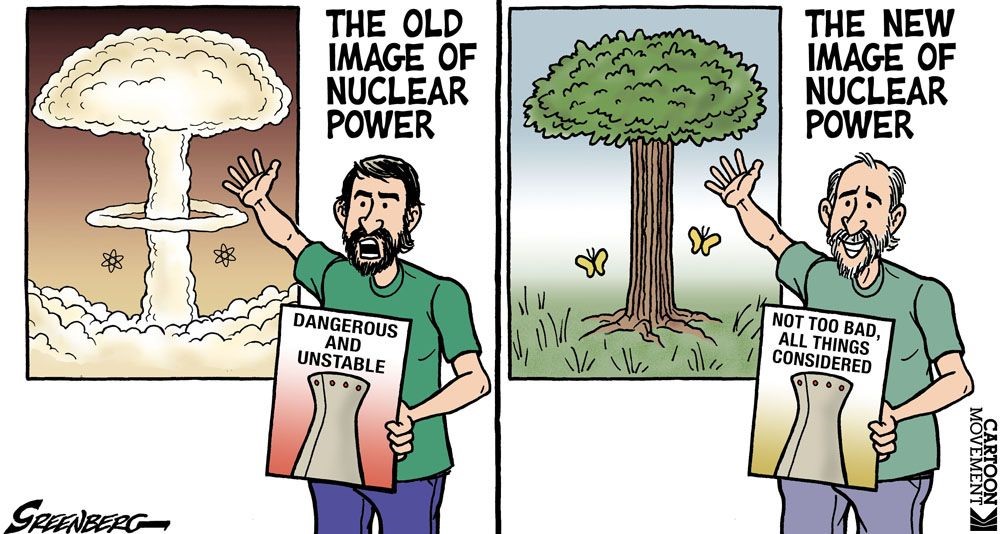

In our world of nuclear power, we know that many have strong views on whether this technology is worthy of being a path to a better world with clean economic abundant energy, or as others believe, is a path to our eventual demise. We have written before about the need to ramp up our communications and work hard to increase support for nuclear power. The facts are on our side, but negative beliefs stand in our way. We are happy to see even more young people come out with supportive communications, from Jarret Adams, to Eric Meyer at Generation Atomic and Bret Kugelmass with his podcast series, Titans of Nuclear; each using their own unique method to promote a nuclear future.

As it is the middle of summer, this is when we love to be a bit more philosophical. It is a time to do some deep thinking while enjoying the sunshine and sharing some more esoteric views based on our reading list so far this year. I have read a few books that I think are useful to both better understand the current environment for communications and provide some useful insights on how to better communicate going forward.

You may think these three books have nothing in common, but I see a common thread that should contribute to our thinking as we move forward. They are “The Death of Expertise: The Campaign Against Established Knowledge and Why it Matters” by Tom Nichols, “Is Gwyneth Paltrow wrong about everything: When Celebrity Culture and Science Clash” by Timothy Caulfield and finally, “If I understood you, would I have this look on my face?: My Adventures in the Art and Science of Relating and Communicating” by Alan Alda.

The first two books provide us with two different but complementary views of the environment we live in. Tom Nichols, in his excellent book, makes the case that America has taken freedom and liberty to an unrealistic extreme – that there is a common belief that everyone is equal and thus, so are their opinions. In fact, he goes so far as to suggest that it is cool to be ignorant. Experts are no longer respected and in fact, he states that “we actively resent them, with many people assuming that experts are wrong simply by virtue of being an expert.”

He talks about the changes to higher education, where young people think they are customers buying a service rather than students given an opportunity to learn. He talks about the changing news media, from provider of unbiased news to “infotainment” and notes that too many people approach the news not to seek information but rather confirmation of what they already know, avoiding sources they disagree with because they believe they are mistaken or even lying (“fake news”).

This book is a must read, with more good quotes than I can use in a short blog post. But if I can summarize in one quote, it would be as follows. “The death of expertise, however, is a different problem than the historical fact of low levels of information among laypeople. The issue is not indifference to established knowledge; it’s the emergence of a positive hostility to such knowledge. This is the new American culture, and it represents the aggressive replacement of expert views or established knowledge with the insistence that every opinion on any matter is as good as every other. “ For everyone in the nuclear industry – sound familiar?

If we don’t listen to experts, then who do we listen to? That is answered in the next book. In his fascinating book on celebrity culture and how it influences us, Timothy Caulfield explores the massive power that celebrities have over our decisions and beliefs. This ranges from using beauty products endorsed by your favourite celebrity (costly but not likely harmful), to using their favourite health care products (costly and may be harmful), to taking bad decisions that can negatively impact the health of our children like avoiding vaccines (definitely harmful).

In summary, we have replaced “experts” who we no longer believe in, with celebrities, who are the ones we look up to. We long for fame rather than accomplishment and dream of achieving it without necessarily working to get there. Anything to be like our idols. Unfortunately, the outcome is often nothing more than an empty wallet and little in terms of being able to take decisions that positively impact our lives.

This takes me to the third book of the bunch, Alan Alda’s book on how to better communicate science. Of course, if we shouldn’t listen to celebrities, then why listen to Alan Alda? It tuns out that he has been involved in communicating science to laypeople for over 20 years, having hosted a show by Scientific American and then starting the Alan Alda Center for communicating science at Stony Brook University. So, what does this book have to say that you may not have heard before? It makes a strong case for communicating, which means having a conversation noting that “real conversation can’t happen if listening is just my waiting for you to finish talking.” It talks about the importance of having empathy for your audience, consistent with many who talk about better communications; but he goes further, saying empathy is not enough; we need to be able to “relate” to our audience. Only then are you really communicating. The book then makes the case for using theatrical improvisation techniques as a means to break down barriers to learn to relate to others.

What can we learn from these books that we can apply to the nuclear industry? Our objective is to change the paradigm on nuclear power and raise awareness of the many benefits it brings to society. To do that let’s first work to improve our approach to communicating. We need to avoid trying to change others’ deeply held beliefs nor try to impose our own beliefs on others. This is a path to nowhere.

Rather, we need to focus on communicating, i.e. having an open and productive conversation with others while working hard to keep open minds. It is a willingness to consider new information that is important for life long learning. Go beyond empathy and truly try to relate. Developing a relationship is hard work but hopefully the outcome will be that we both understand each other better and learn something new.

Moving the needle on public opinion on nuclear power is important and also very challenging. Hopefully some of these perspectives will help us think of new and better ways to have the conversation.

Afterword

For those of you that are interested, the following are a few more quotes from The Death of Expertise. Powerful stuff.

“There is a cult of ignorance in the United States, and there always has been. The strain of anti-intellectualism has been a constant thread winding its way throughout political and cultural life, nurtured by the false notion that democracy means that “my ignorance is just as good as your knowledge.””

“These are dangerous times. Never have so many people had so much access to so much knowledge and yet have been so resistant to learning anything. In the United States and other developed nations, otherwise intelligent people denigrate intellectual achievement and reject the advice of experts. Not only do increasing numbers of laypeople lack basic knowledge, they reject fundamental rules of evidence and refuse to learn how to make a logical argument. In doing so, they risk throwing away centuries of accumulated knowledge and undermining the practices and habits that allow us to develop new knowledge.”

“Rather, Americans now think of democracy as a state of actual equality, in which every opinion is as good as any other on almost any subject under the sun. Feelings are more important than facts: if people think vaccines are harmful, or if they believe that half of the US budget is going to foreign aid, then it is “undemocratic” and “elitist” to contradict them.”