Building nuclear on time and on budget – yes, it is possible…and essential

Large capital projects are hard. They require a huge amount of planning, the logistics are often staggering and depend upon many contractors and suppliers, all who must perform completely in step for everything to come together as planned. The project manager is like the conductor of a large orchestra and as good as all the musicians may be – it only takes one misstep to ruin a beautiful piece of music. Strong leadership and good people are the key.

Nuclear projects are often criticized for being delivered well over cost and schedule. Examples abound. Currently we have the Olkiluoto plant in Finland, the Vogtle plant in Georgia and the Flamanville plant in France all running late and over budget while Watts Bar 2, the first unit to enter service in the USA in 20 years was also recently completed well over its original budget. On the other hand, many plants being built in China and Korea are on time and on budget and even the first new plant in a new nuclear country in a long time, Barakah in the UAE, was built on time and on budget, although there are now some delays in the first unit entering into operations. Of course, nuclear projects are not the only large projects to suffer from overruns. A 2017 report on North American projects by EY Canada has determined that “Canadian infrastructure megaprojects run 39% (US$2.2b) over budget and behind schedule by 12 months on average. However, Canadian megaprojects perform better than those in the US, where the average project delay is a little more than three years.”

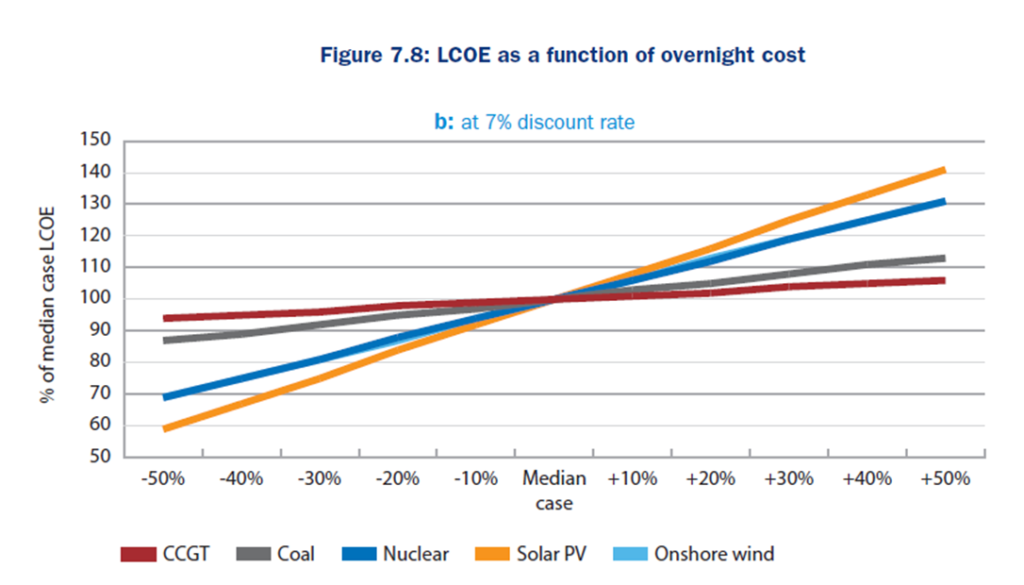

Now, we have talked in the past about the economics of nuclear plants and one thing is clear, the largest component of the cost of energy from a nuclear plant is the capital cost representing about two thirds of the total cost of energy. Therefore, building to budgeted cost and schedule is essential to maintain the estimated economic competitiveness of the plant that was the basis for securing project approval. And because the capital cost is such a large component of the cost of nuclear (and solar) energy, the cost of energy is very sensitive to cost overruns. This can be seen in the chart below from the IEA/NEA report “Projected Costs of Generating Electricity – 2015 edition”.

There are many reasons why large projects go over budget and are late. What is in vogue these days is to put the blame primarily on the fact that these poorly performing projects are First of a Kind (FOAK) projects, meaning they are building a new design for the first time. Other factors include the significant regulatory burden placed on the nuclear industry and the challenges being experienced by a supply chain that has not delivered to a nuclear project in these jurisdictions in a long time and needs to re-establish its capability.

Clearly the strength in the Chinese and Korean programs are from both standardization and the relatively large number of units being built, which provides for more certainty and a well-developed supply chain. And while it is true that doing things for the first time makes a project more difficult, the fact that a project is FOAK may be an explanation but is not a good excuse for the magnitude of overruns we are seeing. If we want to be credible, we must deliver on our commitments. After all, these are large multi-billion dollar projects. While there are many excellent reasons to support nuclear power, who will approve future projects if the outcome is not predictable?

We recently wrote about using fixed price contracts to mitigate some of these risks and why this has resulted in a false sense of security. Today, lets look at some of the things we can do to assess and mitigate the risk of overruns on nuclear projects, primarily those with larger FOAK elements.

Why do we say FOAK elements? Those that know us well, know our complete preoccupation with standardization as a means to controlling project risk. But as much as we would like to say that after the first project the next units will be standard, it is always a matter of degree. For example, the highest level of standardization is when there are multiple units being built at the same site. This allows for everything learned on the first unit to be immediately implemented on the subsequent units by the very same people that have just completed the previous project. Then there is the case where the same design is being implemented on a different site in the same jurisdiction so that most (but not all) of the supply chain and management can also be the same. But for other projects, we know that even when repeating a design, there are many things that can be new or different. Often there are different suppliers and contractors as projects are built in different jurisdictions; and there can also be changes in the financial and contractual structure of the project, that can impact project implementation. And of course, there are always design changes as designs are updated to meet new codes, address site specific issues and meet local regulatory requirements.

As we stated above, large nuclear projects are hard. But hard does not mean impossible. Hard takes the right approach to deliver success. So, what are we to do to deliver projects to time and budget?

We need to all learn from each other. We do not implement enough projects in most jurisdictions to benefit from the series effect on our own. Here are some of the lessons learned gathered from those that have succeeded:

- Plan, plan and plan some more. Nothing is more important than understanding what has to be done before you do it. Large overruns and delays usually come from surprises, i.e. issues that come up that nobody thought about and now take time to resolve when the project clock is ticking.

- Ensure adequate design completion before construction. Understanding scope can only be done when the plant is designed. This is where FOAK plants need a larger investment before the first shovel hits the ground. You cannot plan your project if it is not designed.

- Ready your supply chain. If there are many new suppliers in the mix, or a number have not supplied in a long time, invest in their development and allow time in the program for them to come up to speed.

- Develop and implement a robust risk management program. Identifying and understanding the project risks, and then developing risk mitigation plans are essential to being ready for whatever comes up during project execution. This risk plan should be the basis for project contingencies for both cost and schedule. And even if the risk that comes up was not in the original risk register, having a robust process will ensure that action can be taken quickly and effectively to mitigate and keep the project on track.

- Develop a project financial structure that enables the investment necessary to prepare for the project so that the project plan, estimate and risk program are at a level that can support project success when the project cost and schedule are committed; and finally,

- Get the best possible people you can. We think of large projects as a combination of technology and commodities. But in reality, it is people who build projects and strong leadership is the special sauce that leads to project success.

As we have said many times before, nuclear plants are extremely reliable, efficient, low carbon and cost-effective producers of electricity. As they are capital intensive, their economics depend upon successful project implementation. Project delays and overruns have large impacts on the project economics and negatively impact the credibility of the industry. After all, just like a great symphony, there is something beautiful when a large complex project comes together as planned – and there is nothing more important for the long-term health of the nuclear industry than building projects to cost and schedule.